"Helping woodworkers online for the past 17 Years"

|

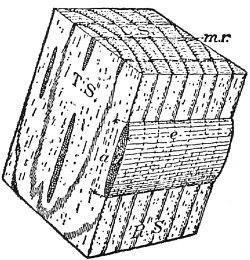

Fig. 4. Block of Oak. CS, cross-section; RS, radial section; TS, tangential section; mr, medullary or pith ray; a, height; b, width; and e, length of pith ray.

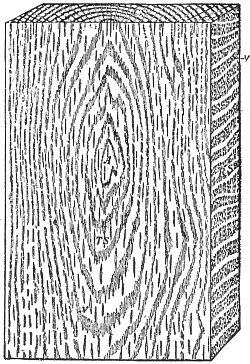

On a cross-section of oak, the same arrangement of pith and bark, of sapwood and heartwood, and the same disposition of the wood in well-defined concentric or annual rings occur, but the rings are marked by lines or rows of conspicuous pores or openings, which occupy the greater part of the spring-wood for each ring (see Fig. 4, also 6), and are, in fact the hollows of vessels through which the cut has been made. On the radial section or quarter-sawn board the several layers appear as so many stripes (see Fig. 5); on the tangential section or "bastard" face patterns similar to those mentioned for pine wood are observed. But while the patterns in hard pine are marked by the darker summer-wood, and are composed of plain, alternating stripes of darker and lighter wood, the figures in oak (and other broad-leaved woods) are due chiefly to the vessels, those of the spring-wood in oak being the most conspicuous (see Fig. 5). So that in an oak table, the darker, shaded parts are the spring-wood, the lighter unicolored parts the summer-wood. On closer examination of the smooth cross-section of oak, the spring-wood part of the ring is found to be formed in great part of pores; large, round, or oval openings made by the cut through long vessels. These are separated by a grayish and quite porous tissue (see Fig. 6, A), which continues here and there in the form of radial, often branched, patches (not the pith rays) into and through the summer-wood to the spring-wood of the next ring. The large vessels of the spring-wood, occupying six to ten per cent of the volume of a log in very good oak, and twenty-five per cent or more in inferior and narrow-ringed timber, are a very important feature, since it is evident that the greater their share in the volume, the lighter and weaker the wood. They are smallest near the pith, and grow wider outward. They are wider in the stem than limb, and seem to be of indefinite length, forming open channels, in some cases probably as long as the tree itself. Scattered through the radiating gray patches of porous wood are vessels similar to those of the spring-wood, but decidedly smaller. These vessels are usually fewer and larger near the outer portions of the ring. Their number and size can be utilized to distinguish the oaks classed as white oaks from those classed as black and red oaks. They are fewer and larger in red oaks, smaller but much more numerous in white oaks. The summer-wood, except for these radial, grayish patches, is dark colored and firm. This firm portion, divided into bodies or strands by these patches of porous wood, and also by fine, wavy, concentric lines of short, thin-walled cells (see Fig. 6, A), consists of thin-walled fibres (see Fig. 7, B), and is the chief element of strength in oak wood. In good white oak it forms one-half or more of the wood, if it cuts like horn, and the cut surface is shiny, and of a deep chocolate brown color. In very narrow-ringed wood and in inferior red oak it is usually much reduced in quantity as well as quality. The pith rays of the oak, unlike those of the coniferous woods, are at least in part very large and conspicuous. (See Fig. 4; their height indicated by the letter a, and their width by the letter b.) The large medullary rays of oak are often twenty and more cells wide, and several hundred cell rows in height, which amount commonly to one or more inches. These large rays are conspicuous on all sections. They appear as long, sharp, grayish lines on the cross-sections; as short, thick lines, tapering at each end, on the tangential or "bastard" face, and as broad, shiny bands, "the mirrors," on the radial section. In addition to these coarse rays, there is also a large number of small pith rays, which can be seen only when magnified. On the whole, the pith rays form a much larger part of the wood than might be supposed. In specimens of good white oak it has been found that they form about sixteen to twenty-five per cent of the wood.

Fig. 5. Board of Oak. CS, cross-section; RS, radial section; TS, tangential section; v, vessels or pores, cut through.; A, slight curve in log which appears in section as an islet.

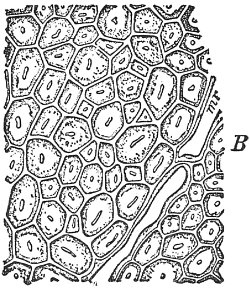

Fig. 7. Portion of the Firm Bodies of Fibres with Two Cells of a Small Pith Ray mr (Highly Magnified).

Fig. 8. Isolated Fibres and Cells, a, four cells of wood, parenchyma; b, two cells from a pith ray; c, a single joint or cell of a vessel, the openings x leading into its upper and lower neighbors; d, tracheid; e, wood fibre proper.

If a well-smoothed thin disk or cross-section of oak (say one-sixteenth inch thick) is held up to the light, it looks very much like a sieve, the pores or vessels appearing as clean-cut holes. The spring-wood and gray patches are seen to be quite porous, but the firm bodies of fibres between them are dense and opaque. Examined with a magnifier it will be noticed that there is no such regularity of arrangement in straight rows as is conspicuous in pine. On the contrary, great irregularity prevails. At the same time, while the pores are as large as pin holes, the cells of the denser wood, unlike those of pine wood, are too small to be distinguished. Studied with the microscope, each vessel is found to be a vertical row of a great number of short, wide tubes, joined end to end (see Fig. 8, c). The porous spring-wood and radial gray tracts are partly composed of smaller vessels, but chiefly of tracheids, like those of pine, and of shorter cells, the "wood parenchyma," resembling the cells of the medullary rays. These latter, as well as the fine concentric lines mentioned as occurring in the summer-wood, are composed entirely of short tube-like parenchyma cells, with square or oblique ends (see Fig. 8, a and b). The wood fibres proper, which form the dark, firm bodies referred to, are very fine, thread-like cells, one twenty-fifth to one-tenth inch long, with a wall commonly so thick that scarcely any empty internal space or lumen remains (see Figs. 8, e, and 7, B). If, instead of oak, a piece of poplar or basswood (see Fig. 9) had been used in this study, the structure would have been found to be quite different. The same kinds of cell-elements, vessels, etc., are, to be sure, present, but their combination and arrangement are different, and thus from the great variety of possible combinations results the great variety of structure and, in consequence, of the qualities which distinguish the wood of broad-leaved trees. The sharp distinction of sap wood and heartwood is wanting; the rings are not so clearly defined; the vessels of the wood are small, very numerous, and rather evenly scattered through the wood of the annual rings, so that the distinction of the ring almost vanishes and the medullary or pith rays in poplar can be seen, without being magnified, only on the radial section.

Woods of complex and very variable structure, and therefore differing widely in quality, behavior, and consequently in applicability to the arts.

1. Ailanthus (Ailanthus glandulosa). Medium to large-sized tree. Wood pale yellow, hard, fine-grained, and satiny. This species originally came from China, where it is known as the Tree of "Heaven," was introduced into the United States and planted near Philadelphia during the 18th century, and is more ornamental than useful. It is used to some extent in cabinet work. Western Pennsylvania and Long Island, New York.

Wood heavy, hard, stiff, quite tough, not durable in contact with the soil, straight-grained, rough on the split surfaces and coarse in texture. The wood shrinks moderately, seasons with little injury, stands well, and takes a good polish. In carpentry, ash is used for stairways, panels, etc. It is used in shipbuilding, in the construction of cars, wagons, etc., in the manufacture of all kinds of farm implements, machinery, and especially of all kinds of furniture; for cooperage, baskets, oars, tool handles, hoops, etc., etc. The trees of the several species of ash are rapid growers, of small to medium height with stout trunks. They form no forests, but occur scattered in almost all our broad-leaved forests.

2. White Ash (Fraxinus Americana). Medium-, sometimes large-sized tree. Heartwood reddish brown, usually mottled; sapwood lighter color, nearly white. Wood heavy, hard, tough, elastic, coarse-grained, compact structure. Annual rings clearly marked by large open pores, not durable in contact with the soil, is straight-grained, and the best material for oars, etc. Used for agricultural implements, tool handles, automobile (rim boards), vehicle bodies and parts, baseball bats, interior finish, cabinet work, etc., etc. Basin of the Ohio, but found from Maine to Minnesota and Texas.

3. Red Ash (Fraxinus pubescens var. Pennsylvanica). Medium-sized tree, a timber very similar to, but smaller than Fraxinus Americana. Heartwood light brown, sapwood lighter color. Wood heavy, hard, strong, and coarse-grained. Ranges from New Brunswick to Florida, and westward to Dakota, Nebraska, and Kansas.

4. Black Ash (Fraxinus nigra var. sambucifolia) (Hoop Ash, Ground Ash). Medium-sized tree, very common, is more widely distributed than the Fraxinus Americana; the wood is not so hard, but is well suited for hoops and basketwork. Heartwood dark brown, sapwood light brown or white. Wood heavy, rather soft, tough and coarse-grained. Used for barrel hoops, basketwork, cabinetwork and interior of houses. Maine to Minnesota and southward to Alabama.

5. Blue Ash (Fraxinus quadrangulata). Small to medium-sized tree. Heartwood yellow, streaked with brown, sapwood a lighter color. Wood heavy, hard, and coarse-grained. Not common. Indiana and Illinois; occurs from Michigan to Minnesota and southward to Alabama.

6. Green Ash (Fraxinus viridis). Small-sized tree. Occurs from New York to the Rocky Mountains, and southward to Florida and Arizona.

7. Oregon Ash (Fraxinus Oregana). Small to medium-sized tree. Occurs from western Washington to California.

8. Carolina Ash (Fraxinus Caroliniana). Medium-sized tree. Occurs in the Carolinas and the coast regions southward.

9. Basswood (Tilia Americana) (Linden, Lime Tree, American Linden, Lin, Bee Tree). Medium- to large-sized tree. Wood light, soft, stiff, but not strong, of fine texture, straight and close-grained, and white to light brown color, but not durable in contact with the soil. The wood shrinks considerably in drying, works well and stands well in interior work. It is used for cooperage, in carpentry, in the manufacture of furniture and woodenware (both turned and carved), for toys, also for panelling of car and carriage bodies, for agricultural implements, automobiles, sides and backs of drawers, cigar boxes, excelsior, refrigerators, trunks, and paper pulp. It is also largely cut for veneer and used as "three-ply" for boxes and chair seats. It is used for sounding boards in pianos and organs. If well seasoned and painted it stands fairly well for outside work. Common in all northern broad-leaved forests. Found throughout the eastern United States, but reaches its greatest size in the Valley of the Ohio, becoming often 130 feet in height, but its usual height is about 70 feet.

10. White Basswood (Tilia heterophylla) (Whitewood). A small-sized tree. Wood in its quality and uses similar to the preceding, only it is lighter in color. Most abundant in the Alleghany region.

11. White Basswood (Tilia pubescens) (Downy Linden, Small-leaved Basswood). Small-sized tree. Wood in its quality and uses similar to Tilia Americana. This is a Southern species which makes it way as far north as Long Island. Is found at its best in South Carolina.

12. Beech (Fagus ferruginea) (Red Beech, White Beech). Medium-sized tree, common, sometimes forming forests of pure growth. Wood heavy, hard, stiff, strong, of rather coarse texture, white to light brown color, not durable in contact with the soil, and subject to the inroads of boring insects. Rather close-grained, conspicuous medullary rays, and when quarter-sawn and well smoothed is very beautiful. The wood shrinks and checks considerably in drying, works well and stands well, and takes a fine polish. Beech is comparatively free from objectionable taste, and finds a place in the manufacture of commodities which come in contact with foodstuffs, such as lard tubs, butter boxes and pails, and the beaters of ice cream freezers; for the latter the persistent hardness of the wood when subjected to attrition and abrasion, while wet gives it peculiar fitness. It is an excellent material for churns. Sugar hogsheads are made of beech, partly because it is a tasteless wood and partly because it has great strength. A large class of woodenware, including veneer plates, dishes, boxes, paddles, scoops, spoons, and beaters, which belong to the kitchen and pantry, are made of this species of wood. Beech picnic plates are made by the million, a single machine turning out 75,000 a day. The wood has a long list of miscellaneous uses and enters in a great variety of commodities. In every region where it grows in commercial quantities it is made into boxes, baskets, and crating. Beech baskets are chiefly employed in shipping fruit, berries, and vegetables. In Maine thin veneer of beech is made specially for the Sicily orange and lemon trade. This is shipped in bulk and the boxes are made abroad. Beech is also an important handle wood, although not in the same class with hickory. It is not selected because of toughness and resiliency, as hickory is, and generally goes into plane, handsaw, pail, chisel, and flatiron handles. Recent statistics show that in the production of slack cooperage staves, only two woods, red gum and pine, stood above beech in quantity, while for heading, pine alone exceeded it. It is also used in turnery, for shoe lasts, butcher blocks, ladder rounds, etc. Abroad it is very extensively used by the carpenter, millwright, and wagon maker, in turnery and wood carving. Most abundant in the Ohio and Mississippi basin, but found from Maine to Wisconsin and southward to Florida.

13. Cherry Birch (Betula lenta) (Black Birch, Sweet Birch, Mahogany Birch, Wintergreen Birch). Medium-sized tree, very common. Wood of beautiful reddish or yellowish brown, and much of it nicely figured, of compact structure, is straight in grain, heavy, hard, strong, takes a fine polish, and considerably used as imitation of mahogany. The wood shrinks considerably in drying, works well and stands well, but is not durable in contact with the soil. The medullary rays in birch are very fine and close and not easily seen. The sweet birch is very handsome, with satiny luster, equalling cherry, and is too costly a wood to be profitably used for ordinary purposes, but there are both high and low grades of birch, the latter consisting chiefly of sapwood and pieces too knotty for first class commodities. This cheap material swells the supply of box lumber, and a little of it is found wherever birch passes through sawmills. The frequent objections against sweet birch as box lumber and crating material are that it is hard to nail and is inclined to split. It is also used for veneer picnic plates and butter dishes, although it is not as popular for this class of commodity as are yellow and paper birch, maple and beech. The best grades are largely used for furniture and cabinet work, and also for interior finish. Maine to Michigan and to Tennessee.

14. White Birch (Betula populifolia) (Gray Birch, Old Field Birch, Aspen-leaved Birch). Small to medium-sized tree, least common of all the birches. Short-lived, twenty to thirty feet high, grows very rapidly. Heartwood light brown, sapwood lighter color. Wood light, soft, close-grained, not strong, checks badly in drying, decays quickly, not durable in contact with the soil, takes a good polish. Used for spools, shoepegs, wood pulp, and barrel hoops. Fuel, value not high, but burns with bright flame. Ranges from Nova Scotia and lower St. Lawrence River, southward, mostly in the coast region to Delaware, and westward through northern New England and New York to southern shore of Lake Ontario.

15. Yellow Birch (Betula lutea) (Gray Birch, Silver Birch). Medium- to large-sized tree, very common. Heartwood light reddish brown, sapwood nearly white, close-grained, compact structure, with a satiny luster. Wood heavy, very strong, hard, tough, susceptible of high polish, not durable when exposed. Is similar to Betula lenta, and finds a place in practically all kinds of woodenware. A large percentage of broom handles on the market are made of this species of wood, though nearly every other birch contributes something. It is used for veneer plates and dishes made for pies, butter, lard, and many other commodities. Tubs and pails are sometimes made of yellow birch provided weight is not objectionable. The wood is twice as heavy as some of the pines and cedars. Many small handles for such articles as flatirons, gimlets, augers, screw drivers, chisels, varnish and paint brushes, butcher and carving knives, etc. It is also widely used for shipping boxes, baskets, and crates, and it is one of the stiffest, strongest woods procurable, but on account of its excessive weight it is sometimes discriminated against. It is excellent for veneer boxes, and that is probably one of the most important places it fills. Citrus fruit from northern Africa and the islands and countries of the Mediterranean is often shipped to market in boxes made of yellow birch from veneer cut in New England. The better grades are also used for furniture and cabinet work, and the "burls" found on this species are highly valued for making fancy articles, gavels, etc. It is extensively used for turnery, buttons, spools, bobbins, wheel hubs, etc. Maine to Minnesota and southward to Tennessee.

16. Red Birch (Betula rubra var. nigra) (River Birch). Small to medium-sized tree, very common. Lighter and less valuable than the preceding. Heartwood light brown, sapwood pale. Wood light, fairly strong and close-grained. Red birch is best developed in the middle South, and usually grows near the banks of rivers. Its bark hangs in tatters, even worse than that of paper birch, but it is darker. In Tennessee the slack coopers have found that red birch makes excellent barrel heads and it is sometimes employed in preference to other woods. In eastern Maryland the manufacturers of peach baskets draw their supplies from this wood, and substitute it for white elm in making the hoops or bands which stiffen the top of the basket, and provide a fastening for the veneer which forms the sides. Red birch bends in a very satisfactory manner, which is an important point. This wood enters pretty generally into the manufacture of woodenware within its range, but statistics do not mention it by name. It is also used in the manufacture of veneer picnic plates, pie plates, butter dishes, washboards, small handles, kitchen and pantry utensils, and ironing boards. New England to Texas and Missouri.

17. Canoe Birch (Betula paprifera) (White Birch, Paper Birch). Small to medium-sized tree, sometimes forming forests, very common. Heartwood light brown tinged with red, sapwood lighter color. Wood of good quality, but light, fairly hard and strong, tough, close-grained. Sap flows freely in spring and by boiling can be made into syrup. Not as valuable as any of the preceding. Canoe birch is a northern tree, easily identified by its white trunk and its ragged bark. Large numbers of small wooden boxes are made by boring out blocks of this wood, shaping them in lathes, and fitting lids on them. Canoe birch is one of the best woods for this class of commodities, because it can be worked very thin, does not split readily, and is of pleasing color. Such boxes, or two-piece diminutive kegs, are used as containers for articles shipped and sold in small bulk, such as tacks, small nails, and brads. Such containers are generally cylindrical and of considerably greater depth than diameter. Many others of nearly similar form are made to contain ink bottles, bottles of perfumery, drugs, liquids, salves, lotions, and powders of many kinds. Many boxes of this pattern are used by manufacturers of pencils and crayons for packing and shipping their wares. Such boxes are made in numerous numbers by automatic machinery. A single machine of the most improved pattern will turn out 1,400 boxes an hour. After the boring and turning are done, they are smoothed by placing them into a tumbling barrel with soapstone. It is also used for one-piece shallow trays or boxes, without lids, and used as card receivers, pin receptacles, butter boxes, fruit platters, and contribution plates in churches. It is also the principal wood used for spools, bobbins, bowls, shoe lasts, pegs, and turnery, and is also much used in the furniture trade. All along the northern boundary of the United States and northward, from the Atlantic to the Pacific.

18. Blue Beech (Carpinus Caroliniana) (Hornbeam, Water Beech, Ironwood). Small-sized tree. Heartwood light brown, sapwood nearly white. Wood very hard, heavy, strong, very stiff, of rather fine texture, not durable in contact with the soil, shrinks and checks considerably in drying, but works well and stands well, and takes a fine polish. Used chiefly in turnery, for tool handles, etc. Abroad much used by mill- and wheelwrights. A small tree, largest in the Southwest, but found in nearly all parts of the eastern United States.

Wood light, soft, not strong, often quite tough, of fine, uniform texture and creamy white color. It shrinks considerably in drying, but works well and stands well. Used for woodenware, artificial limbs, paper pulp, and locally also for building construction.

19. Ohio Buckeye (Æsculus glabra) (Horse Chestnut, Fetid Buckeye). Small-sized tree, scattered, never forming forests. Heartwood white, sapwood pale brown. Wood light, soft, not strong, often quite tough and close-grained. Alleghanies, Pennsylvania to Oklahoma.

20. Sweet Buckeye (Æsculus octandra var. flava) (Horse Chestnut). Small-sized tree, scattered, never forming forests. Wood in its quality and uses similar to the preceding. Alleghanies, Pennsylvania to Texas.

21. Buckthorne (Rhanmus Caroliniana) (Indian Cherry). Small-sized tree. Heartwood light brown, sapwood almost white. Wood light, hard, close-grained. Does not enter the markets to any great extent. Found along the borders of streams in rich bottom lands. Its northern limits is Long Island, where it is only a shrub; it becomes a tree only in southern Arkansas and adjoining regions.

22. Butternut (Juglans cinerea) (White Walnut, White Mahogany, Walnut). Medium-sized tree, scattered, never forming forests. Wood very similar to black walnut, but light, quite soft, and not strong. Heartwood light gray-brown, darkening with exposure; sapwood nearly white, coarse-grained, compact structure, easily worked, and susceptible to high polish. Has similar grain to black walnut and when stained is a very good imitation. Is much used for inside work, and very durable. Used chiefly for finishing lumber, cabinet work, boat finish and fixtures, and for furniture. Butternut furniture is often sold as circassian walnut. Largest and most common in the Ohio basin. Maine to Minnesota and southward to Georgia and Alabama.

The catalpa is a tree which was planted about 25 years ago as a commercial speculation in Iowa, Kansas, and Nebraska. Its native habitat was along the rivers Ohio and lower Wabash, and a century ago it gained a reputation for rapid growth and durability, but did not grow in large quantities. As a railway tie, experiments have left no doubt as to its resistance to decay; it stands abrasion as well as the white oak (Quercus alba), and is superior to it in longevity. Catalpa is a tree singularly free from destructive diseases. Wood cut from the living tree is one of the most durable timbers known. In spite of its light porous structure it resists the weathering influences and the attacks of wood-destroying fungi to a remarkable degree. No fungus has yet been found which will grow in the dead timber, and for fence posts this wood has no equal, lasting longer than almost any other species of timber. The wood is rather soft and coarse in texture, the tree is of slow growth, and the brown colored heartwood, even of very young trees, forms nearly three-quarters of their volume. There is only about one-quarter inch of sapwood in a 9-inch tree.

23. Catalpa (Catalpa speciosa var. bignonioides) (Indian Bean). Medium-sized tree. Heartwood light brown, sapwood nearly white. Wood light, soft, not strong, brittle, very durable in contact with the soil, of coarse texture. Used chiefly for railway ties, telegraph poles, and fence posts, but well suited for a great variety of uses. Lower basin of the Ohio River, locally common. Extensively planted, and therefore promising to become of some importance.

24. Cherry (Prunus serotina) (Wild Cherry, Black Cherry, Rum Cherry). Wood heavy, hard, strong, of fine texture. Sapwood yellowish white, heartwood reddish to brown. The wood shrinks considerably in drying, works well and stands well, has a fine satin-like luster, and takes a fine polish which somewhat resembles mahogany, and is much esteemed for its beauty. Cherry is chiefly used as a decorative interior finishing lumber, for buildings, cars and boats, also for furniture and in turnery, for musical instruments, walking sticks, last blocks, and woodenware. It is becoming too costly for many purposes for which it is naturally well suited. The lumber-furnishing cherry of the United States, the wild black cherry, is a small to medium-sized tree, scattered through many of the broad-leaved trees of the western slope of the Alleghanies, but found from Michigan to Florida, and west to Texas. Other species of this genus, as well as the hawthornes (Prunus cratoegus) and wild apple (Pyrus), are not commonly offered in the markets. Their wood is of the same character as cherry, often finer, but in smaller dimensions.

25. Red Cherry (Prunus Pennsylvanica) (Wild Red Cherry, Bird Cherry). Small-sized tree. Heartwood light brown, sapwood pale yellow. Wood light, soft, and close-grained. Uses similiar to the preceding, common throughout the Northern States, reaching its greatest size on the mountains of Tennessee.

The chestnut is a long-lived tree, attaining an age of from 400 to 600 years, but trees over 100 years are usually hollow. It grows quickly, and sprouts from a chestnut stump (Coppice Chestnut) often attain a height of 8 feet in the first year. It has a fairly cylindrical stem, and often grows to a height of 100 feet and over. Coppice chestnut, that is, chestnut grown on an old stump, furnishes better timber for working than chestnut grown from the nut, it is heavier, less spongy, straighter in grain, easier to split, and stands exposure longer.

26. Chestnut (Castanea vulgaris var. Americana). Medium- to large-sized tree, never forming forests. Wood is light, moderately hard, stiff, elastic, not strong, but very durable when in contact with the soil, of coarse texture. Sapwood light, heartwood darker brown, and is readily distinguishable from the sapwood, which very early turns into heartwood. It shrinks and checks considerably in drying, works easily, stands well. The annual rings are very distinct, medullary rays very minute and not visible to the naked eye. Used in cooperage, for cabinetwork, agricultural implements, railway ties, telegraph poles, fence posts, sills, boxes, crates, coffins, furniture, fixtures, foundation for veneer, and locally in heavy construction. Very common in the Alleghanies. Occurs from Maine to Michigan and southward to Alabama.

27. Chestnut (Castanea dentata var. vesca). Medium-sized tree, never forming forests, not common. Heartwood brown color, sapwood lighter shade, coarse-grained. Wood and uses similar to the preceding. Occurs scattered along the St. Lawrence River, and even there is met with only in small quantities.

28. Chinquapin (Castanea pumila). Medium- to small-sized tree, with wood slightly heavier, but otherwise similiar to the preceding. Most common in Arkansas, but with nearly the same range as Castanea vulgaris.

29. Chinquapin (Castanea chrysophylla). A medium-sized tree of the western ranges of California and Oregon.

30. Coffee Tree (Gymnocladus dioicus) (Coffee Nut, Stump Tree). A medium- to large-sized tree, not common. Wood heavy, hard, strong, very stiff, of coarse texture, and durable. Sapwood yellow, heartwood reddish brown, shrinks and checks considerably in drying, works well and stands well, and takes a fine polish. It is used to a limited extent in cabinetwork and interior finish. Pennsylvania to Minnesota and Arkansas.

31. Crab Apple (Pyrus coronaria) (Wild Apple, Fragrant Crab). Small-sized tree. Heartwood reddish brown, sapwood yellow. Wood heavy, hard, not strong, close-grained. Used principally for tool handles and small domestic articles. Most abundant in the middle and western states, reaches its greatest size in the valleys of the lower Ohio basin.

32. Dogwood (Cornus florida) (American Box). Small to medium-sized tree. Attains a height of about 30 feet and about 12 inches in diameter. The heartwood is a red or pinkish color, the sapwood, which is considerable, is a creamy white. The wood has a dull surface and very fine grain. It is valuable for turnery, tool handles, and mallets, and being so free from silex, watchmakers use small splinters of it for cleaning out the pivot holes of watches, and opticians for removing dust from deep-seated lenses. It is also used for butchers' skewers, and shuttle blocks and wheel stock, and is suitable for turnery and inlaid work. Occurs scattered in all the broad-leaved forests of our country; very common.

Wood heavy, hard, strong, elastic, very tough, moderately durable in contact with the soil, commonly cross-grained, difficult to split and shape, warps and checks considerably in drying, but stands well if properly seasoned. The broad sapwood whitish, heartwood light brown, both with shades of gray and red. On split surfaces rough, texture coarse to fine, capable of high polish. Elm for years has been the principal wood used in slack cooperage for barrel staves, also in the construction of cars, wagons, etc., in boat building, agricultural implements and machinery, in saddlery and harness work, and particularly in the manufacture of all kinds of furniture, where the beautiful figures, especially those of the tangential or bastard section, are just beginning to be appreciated. The elms are medium- to large-sized trees, of fairly rapid growth, with stout trunks; they form no forests of pure growth, but are found scattered in all the broad-leaved woods of our country, sometimes forming a considerable portion of the arborescent growth.

33. White Elm (Ulmus Americana) (American Elm, Water Elm). Medium- to large-sized tree. Wood in its quality and uses as stated above. Common. Maine to Minnesota, southward to Florida and Texas.

34. Rock Elm (Ulmus racemosa) (Cork Elm, Hickory Elm, White Elm, Cliff Elm). Medium- to large-sized tree of rapid growth. Heartwood light brown, often tinged with red, sapwood yellowish or greenish white, compact structure, fibres interlaced. Wood heavy, hard, very tough, strong, elastic, difficult to split, takes a fine polish. Used for agricultural implements, automobiles, crating, boxes, cooperage, tool handles, wheel stock, bridge timbers, sills, interior finish, and maul heads. Fairly free from knots and has only a small quantity of sapwood. Michigan, Ohio, from Vermont to Iowa, and southward to Kentucky.

35. Red Elm (Ulmus fulva var. pubescens) (Slippery Elm, Moose Elm). The red or slippery elm is not as large a tree as the white elm (Ulmus Americana), though it occasionally attains a height of 135 feet and a diameter of 4 feet. It grows tall and straight, and thrives in river valleys. The wood is heavy, hard, strong, tough, elastic, commonly cross-grained, moderately durable in contact with the soil, splits easily when green, works fairly well, and stands well if properly handled. Careful seasoning and handling are essential for the best results. Trees can be utilized for posts when very small. When green the wood rots very quickly in contact with the soil. Poles for posts should be cut in summer and peeled and dried before setting. The wood becomes very tough and pliable when steamed, and is of value for sleigh runners and for ribs of canoes and skiffs. Together with white elm (Ulmus Americana) it is extensively used for barrel staves in slack cooperage and also for furniture. The thick, viscous inner bark, which gives the tree its descriptive name, is quite palatable, slightly nutritious, and has a medicinal value. Found chiefly along water courses. New York to Minnesota, and southward to Florida and Texas.

36. Cedar Elm (Ulmus crassifolia). Medium- to small-sized tree, locally quite common. Arkansas and Texas.

37. Winged Elm (Ulmus alata) (Wahoo). Small-sized tree, locally quite common. Heartwood light brown, sapwood yellowish white. Wood heavy, hard, tough, strong, and close-grained. Arkansas, Missouri, and eastern Virginia.

This general term applies to three important species of gum in the South, the principal one usually being distinguished as "red" or "sweet" gum . The next in importance being the "tupelo" or "bay poplar," and the least of the trio is designated as "black" or "sour" gum. Up to the year 1900 little was known of gum as a wood for cooperage purposes, but by the continued advance in price of the woods used, a few of the most progressive manufacturers, looking into the future, saw that the supply of the various woods in use was limited, that new woods would have to be sought, and gum was looked upon as a possible substitute, owing to its cheapness and abundant supply. No doubt in the future this wood will be used to a considerable extent in the manufacture of both "tight" and "slack" cooperage. In the manufacture of the gum, unless the knives and saws are kept very sharp, the wood has a tendency to break out, the corners splitting off; and also, much difficulty has been experienced in seasoning and kiln-drying.

In the past, gum, having no marketable value, has been left standing after logging operations, or, where the land has been cleared for farming, the trees have been "girdled" and allowed to rot, and then felled and burned as trash. Now, however, that there is a market for this species of timber, it will be profitable to cut the gum with the other hardwoods, and this species of wood will come in for a greater share of attention than ever before.

38. Red Gum (Liquidamber styraciflua) (Sweet Gum, Hazel Pine, Satin Walnut, Liquidamber, Bilsted). The wood is about as stiff and as strong as chestnut, rather heavy, it splits easily and is quite brash, commonly cross-grained, of fine texture, and has a large proportion of whitish sapwood, which decays rapidly when exposed to the weather; but the reddish brown heartwood is quite durable, even in the ground. The external appearance of the wood is of fine grain and smooth, close texture, but when broken the lines of fracture do not run with apparent direction of the growth; possibly it is this unevenness of grain which renders the wood so difficult to dry without twisting and warping. It has little resiliency; can be easily bent when steamed, and when properly dried will hold its shape. The annual rings are not distinctly marked, medullary rays fine and numerous. The green wood contains much water, and consequently is heavy and difficult to float, but when dry it is as light as basswood. The great amount of water in the green wood, particularly in the sap, makes it difficult to season by ordinary methods without warping and twisting. It does not check badly, is tasteless and odorless, and when once seasoned, swells and shrinks but little unless exposed to the weather. Used for boat finish, veneers, cabinet work, furniture, fixtures, interior decoration, shingles, paving blocks, woodenware, cooperage, machinery frames, refrigerators, and trunk slats.

Red gum is distributed from Fairfield County, Conn., to southeastern Missouri, through Arkansas and Oklahoma to the valley of the Trinity River in Texas, and eastward to the Atlantic coast. Its commercial range is restricted, however, to the moist lands of the lower Ohio and Mississippi basins and of the Southeastern coast. It is one of the commonest timber trees in the hardwood bottoms and drier swamps of the South. It grows in mixture with ash, cottonwood and oak (see Fig. 12). It is also found to a considerable extent on the lower ridges and slopes of the southern Appalachians, but there it does not reach merchantable value and is of little importance. Considerable difference is found between the growth in the upper Mississippi bottoms and that along the rivers on the Atlantic coast and on the Gulf. In the latter regions the bottoms are lower, and consequently more subject to floods and to continued overflows (see Fig. 11). The alluvial deposit is also greater, and the trees grow considerably faster. Trees of the same diameter show a larger percentage of sapwood there than in the upper portions of the Mississippi Valley. The Mississippi Valley hardwood trees are for the most part considerably older, and reach larger dimensions than the timber along the coast.

In the best situations red gum reaches a height of 150 feet, and a diameter of 5 feet. These dimensions, however are unusual. The stem is straight and cylindrical, with dark, deeply-furrowed bark, and branches often winged with corky ridges. In youth, while growing vigorously under normal conditions, it assumes a long, regular, conical crown, much resembling the form of a conifer (see Fig. 12). After the tree has attained its height growth, however, the crown becomes rounded, spreading and rather ovate in shape. When growing in the forest the tree prunes itself readily at an early period, and forms a good length of clear stem, but it branches strongly after making most of its height growth. The mature tree is usually forked, and the place where the forking commences determines the number of logs in the tree or its merchantable length, by preventing cutting to a small diameter in the top. On large trees the stem is often not less than eighteen inches in diameter where the branching begins. The over-mature tree is usually broken and dry topped, with a very spreading crown, in consequence of new branches being sent out.

Throughout its entire life red gum is intolerant in shade, there are practically no red seedlings under the dense forest cover of the bottom land, and while a good many may come up under the pine forest on the drier uplands, they seldom develop into large trees. As a rule seedlings appear only in clearings or in open spots in the forest. It is seldom that an over-topped tree is found, for the gum dies quickly if suppressed, and is consequently nearly always a dominant or intermediate tree. In a hardwood bottom forest the timber trees are all of nearly the same age over considerable areas, and there is little young growth to be found in the older stands. The reason for this is the intolerance of most of the swamp species. A scale of intolerance containing the important species, and beginning with the most light-demanding, would run as follows: Cottonwood, sycamore, red gum, white elm, white ash, and red maple.

While the red gum grows in various situations, it prefers the deep, rich soil of the hardwood bottoms, and there reaches its best development (see Fig. 10). It requires considerable soil moisture, though it does not grow in the wetter swamps, and does not thrive on dry pine land. Seedlings, however, are often found in large numbers on the edges of the uplands and even on the sandy pine land, but they seldom live beyond the pole stage. When they do, they form small, scrubby trees that are of little value. Where the soil is dry the tree has a long tap root. In the swamps, where the roots can obtain water easily, the development of the tap root is poor, and it is only moderate on the glade bottom lands, where there is considerable moisture throughout the year, but no standing water in the summer months.

Red gum reproduces both by seed and by sprouts. It produces seed fairly abundantly every year, but about once in three years there is an extremely heavy production. The tree begins to bear seed when twenty-five to thirty years old, and seeds vigorously up to an age of one hundred and fifty years, when its productive power begins to diminish. A great part of the seed, however, is abortive. Red gum is not fastidious in regard to its germinating bed; it comes up readily on sod in old fields and meadows, on decomposing humus in the forest, or on bare clay-loam or loamy sand soil. It requires a considerable degree of light, however, and prefers a moist seed bed. The natural distribution of the seed takes place for several hundred feet from the seed trees, the dissemination depending almost entirely on the wind. A great part of the seed falls on the hardwood bottom when the land is flooded, and is either washed away or, if already in the ground and germinating, is destroyed by the long-continued overflow. After germinating, the red gum seedling demands, above everything else, abundant light for its survival and development. It is for this reason that there is very little growth of red gum, either in the unculled forest or on culled land, where, as is usually the case, a dense undergrowth of cane, briers, and rattan is present. Under the dense underbrush of cane and briers throughout much of the virgin forest, reproduction of any of the merchantable species is of course impossible. And even where the land has been logged over, the forest is seldom open enough to allow reproduction of cottonwood and red gum. Where, however, seed trees are contiguous to pastures or cleared land, scattered seedlings are found springing up in the open, and where openings occur in the forest, there are often large numbers of red gum seedlings, the reproduction generally occurring in groups. But over the greater part of the Southern hardwood bottom land forest reproduction is very poor. The growth of red gum during the early part of its life, and up to the time it reaches a diameter of eight inches breast-high, is extremely rapid, and, like most of the intolerant species, it attains its height growth at an early period. Gum sprouts readily from the stump, and the sprouts surpass the seedlings in rate of height growth for the first few years, but they seldom form large timber trees. Those over fifty years of age seldom sprout. For this reason sprout reproduction is of little importance in the forest. The principal requirements of red gum, then, are a moist, fairly rich soil and good exposure to light. Without these it will not reach its best development.

Second-growth red gum occurs to any considerable extent only on land which has been thoroughly cleared. Throughout the South there is a great deal of land which was in cultivation before the Civil War, but which during the subsequent period of industrial depression was abandoned and allowed to revert to forest. These old fields now mostly covered with second-growth forest, of which red gum forms an important part. Frequently over fifty per cent of the stand consists of this species, but more often, and especially on the Atlantic coast, the greater part is of cottonwood or ash. These stands are very dense, and the growth is extremely rapid. Small stands of young growth are also often found along the edges of cultivated fields. In the Mississippi Valley the abandoned fields on which young stands have sprung up are for the most part being rapidly cleared again. The second growth here is considered of little value in comparison with the value of the land for agricultural purposes. In many cases, however, the farm value of the land is not at present sufficient to make it profitable to clear it, unless the timber cut will at least pay for the operation. There is considerable land upon which the second growth will become valuable timber within a few years. Such land should not be cleared until it is possible to utilize the timber.

39. Tupelo Gum (Nyssa aquatica) (Bay Poplar, Swamp Poplar, Cotton Gum, Hazel Pine, Circassian Walnut, Pepperidge, Nyssa). The close similarity which exists between red and tupelo gum, together with the fact that tupelo is often cut along with red gum, and marketed with the sapwood of the latter, makes it not out of place to give consideration to this timber. The wood has a fine, uniform texture, is moderately hard and strong, is stiff, not elastic, very tough and hard to split, but easy to work with tools. Tupelo takes glue, paint, or varnish well, and absorbs very little of the material. In this respect it is equal to yellow poplar and superior to cottonwood. The wood is not durable in contact with ground, and requires much care in seasoning. The distinction between the heartwood and sapwood of this species is marked. The former varies in color from a dull gray to a dull brown; the latter is whitish or light yellow like that of poplar. The wood is of medium weight, about thirty-two pounds per cubic foot when dry, or nearly that of red gum and loblolly pine. After seasoning it is difficult to distinguish the better grades of sapwood from poplar. Owing to the prejudice against tupelo gum, it was until recently marketed under such names as bay poplar, swamp poplar, nyssa, cotton gum, circassian walnut, and hazel pine. Since it has become evident that the properties of the wood fit it for many uses, the demand for tupelo has largely increased, and it is now taking rank with other standard woods under its rightful name. Heretofore the quality and usefulness of this wood were greatly underestimated, and the difficulty of handling it was magnified. Poor success in seasoning and kiln-drying was laid to defects of the wood itself, when, as a matter of fact, the failures were largely due to the absence of proper methods in handling. The passing of this prejudice against tupelo is due to a better understanding of the characteristics and uses of the wood. Handled in the way in which its particular character demands, tupelo is a wood of much value.

Tupelo gum is now used in slack cooperage, principally for heading. It is used extensively for house flooring and inside finishing, such as mouldings, door jambs, and casings. A great deal is now shipped to European countries, where it is highly valued for different classes of manufacture. Much of the wood is used in the manufacture of boxes, since it works well upon rotary veneer machines. There is also an increasing demand for tupelo for laths, wooden pumps, violin and organ sounding boards, coffins, mantelwork, conduits and novelties. It is also used in the furniture trade for backing, drawers, and panels.

Tupelo occurs throughout the coastal region of the Atlantic States, from southern Virginia to northern Florida, through the Gulf States to the valley of the Nueces River in Texas, through Arkansas and southern Missouri to western Kentucky and Tennessee, and to the valley of the lower Wabash River. Tupelo is being extensively milled at present only in the region adjacent to Mobile Ala., and in southern and central Louisiana, where it occurs in large merchantable quantities, attaining its best development in the former locality. The country in this locality is very swampy, and within a radius of one hundred miles tupelo gum is one of the principal timber trees. It grows only in the swamps and wetter situations, often in mixture with cypress, and in the rainy season it stands in from two to twenty feet of water.

40. Black Gum (Nyssa sylvatica) (Sour Gum). Black gum is not cut to much extent, owing to its less abundant supply and poorer quality, but is used for repair work on wagons, for boxes, crates, wagon hubs, rollers, bowls, woodenware, and for cattle yokes and other purposes which require a strong, non-splitting wood. Heartwood is light brown in color, often nearly white; sapwood hardly distinguishable, fine grain, fibres interwoven. Wood is heavy, not hard, difficult to work, strong, very tough, checks and warps considerably in drying, not durable. It is distributed from Maine to southern Ontario, through central Michigan to southeastern Missouri, southward to the valley of the Brazos River in Texas, and eastward to the Kissimmee River and Tampa Bay in Florida. It is found in the swamps and hardwood bottoms, but is more abundant and of better size on the slightly higher ridges and hummocks in these swamps, and on the mountain slopes in the southern Alleghany region. Though its range is greater than that of either red or tupelo gum, it nowhere forms an important part of the forest.

41. Hackberry (Celtis occidentalis) (Sugar Berry, Nettle Tree). The wood is handsome, heavy, hard, strong, quite tough, of moderately fine texture, and greenish or yellowish color, shrinks moderately, works well and stands well, and takes a good polish. Used to some extent in cooperage, and in the manufacture of cheap furniture. Medium- to large-sized tree, locally quite common, largest in the lower Mississippi Valley. Occurs in nearly all parts of the eastern United States.

The hickories of commerce are exclusively North American and some of them are large and beautiful trees of 60 to 70 feet or more in height. They are closely allied to the walnut, and the wood is very like walnut in grain and color, though of a somewhat darker brown. It is one of the finest of American hardwoods in point of strength; in toughness it is superior to ash, rather coarse in texture, smooth and of straight grain, very heavy and strong as well as elastic and tenacious, but decays rapidly, especially the sapwood when exposed to damp and moisture, and is very liable to attack from worms and boring insects. The cross-section of hickory is peculiar, the annual rings appear like fine lines instead of like the usual pores, and the medullary rays, which are also very fine but distinct, in crossing these form a peculiar web-like pattern which is one of the characteristic differences between hickory and ash. Hickory is rarely subjected to artificial treatment, but there is this curious fact in connection with the wood, that, contrary to most other woods, creosote is only with difficulty injected into the sap, although there is no difficulty in getting it into the heartwood. It dries slowly, shrinks and checks considerably in seasoning; is not durable in contact with the soil or if exposed. Hickory excels as wagon and carriage stock, for hoops in cooperage, and is extensively used in the manufacture of implements and machinery, for tool handles, timber pins, harness work, dowel pins, golf clubs, and fishing rods. The hickories are tall trees with slender stems, never forming forests, occasionally small groves, but usually occur scattered among other broad-leaved trees in suitable localities. The following species all contribute more or less to the hickory of the markets:

42. Shagbark Hickory (Hicoria ovata) (Shellbark Hickory, Scalybark Hickory). A medium- to large-sized tree, quite common; the favorite among the hickories. Heartwood light brown, sapwood ivory or cream-colored. Wood close-grained, compact structure, annual rings clearly marked. Very hard, heavy, strong, tough, and flexible, but not durable in contact with the soil or when exposed. Used for agricultural implements, wheel runners, tool handles, vehicle parts, baskets, dowel pins, harness work, golf clubs, fishing rods, etc. Best developed in the Ohio and Mississippi basins; from Lake Ontario to Texas, Minnesota to Florida.

43. Mockernut Hickory (Hicoria alba) (Black Nut Hickory, Black Hickory, Bull Nut Hickory, Big Bud Hickory, White Heart Hickory). A medium- to large-sized tree. Wood in its quality and uses similar to the preceding. Its range is the same as that of Hicoria ovata. Common, especially in the South.

44. Pignut Hickory (Hicoria glabra) (Brown Hickory, Black Hickory, Switchbud Hickory). A medium- to large-sized tree. Heavier and stronger than any of the preceding. Heartwood light to dark brown, sapwood nearly white. Abundant, all eastern United States.

45. Bitternut Hickory (Hicoria minima) (Swamp Hickory). A medium-sized tree, favoring wet localities. Heartwood light brown, sapwood lighter color. Wood in its quality and uses not so valuable as Hicoria ovata, but is used for the same purposes. Abundant, all eastern United States.

46. Pecan (Hicoria pecan) (Illinois Nut). A large tree, very common in the fertile bottoms of the western streams. Indiana to Nebraska and southward to Louisiana and Texas.

47. Holly (Ilex opaca). Small to medium-sized tree. Wood of medium weight, hard, strong, tough, of exceedingly fine grain, closer in texture than most woods, of white color, sometimes almost as white as ivory; requires great care in its treatment to preserve the whiteness of the wood. It does not readily absorb foreign matter. Much used by turners and for all parts of musical instruments, for handles on whips and fancy articles, draught-boards, engraving blocks, cabinet work, etc. The wood is often dyed black and sold as ebony; works well and stands well. Most abundant in the lower Mississippi Valley and Gulf States, but occurring eastward to Massachusetts and north to Indiana.

48. Holly (Ilex monticolo) (Mountain Holly). Small-sized tree. Wood in its quality and uses similar to the preceding, but is not very generally known. It is found in the Catskill Mountains and extends southward along the Alleghanies as far as Alabama.

49. Ironwood (Ostrya Virginiana) (Hop Hornbeam, Lever Wood). Small-sized tree, common. Heartwood light brown tinged with red, sapwood nearly white. Wood heavy, tough, exceedingly close-grained, very strong and hard, durable in contact with the soil, and will take a fine polish. Used for small articles like levers, handles of tools, mallets, etc. Ranges throughout the United States east of the Rocky Mountains.

50. Laurel (Umbellularia Californica) (Myrtle). A Western tree, produces timber of light brown color of great size and beauty, and is very valuable for cabinet and inside work, as it takes a fine polish. California and Oregon, coast range of the Sierra Nevada Mountains.

51. Black Locust (Robinia pseudacacia) (Locust, Yellow Locust, Acacia). Small to medium-sized tree. Wood very heavy, hard, strong, and tough, rivalling some of the best oak in this latter quality. The wood has great torsional strength, excelling most of the soft woods in this respect, of coarse texture, close-grained and compact structure, takes a fine polish. Annual rings clearly marked, very durable in contact with the soil, shrinks and checks considerably in drying, the very narrow sapwood greenish yellow, the heartwood brown, with shades of red and green. Used for wagon hubs, trenails or pins, but especially for railway ties, fence posts, and door sills. Also used for boat parts, turnery, ornamentations, and locally for construction. Abroad it is much used for furniture and farming implements and also in turnery. At home in the Alleghany Mountains, extensively planted, especially in the West.

52. Honey Locust (Gleditschia triacanthos) (Honey Shucks, Locust, Black Locust, Brown Locust, Sweet Locust, False Acacia, Three-Thorned Acacia). A medium-sized tree. Wood heavy, hard, strong, tough, durable in contact with the soil, of coarse texture, susceptible to a good polish. The narrow sapwood yellow, the heartwood brownish red. So far, but little appreciated except for fences and fuel. Used to some extent for wheel hubs, and locally in rough construction. Found from Pennsylvania to Nebraska, and southward to Florida and Texas; locally quite abundant.

53. Locust (Robinia viscosa) (Clammy Locust). Usually a shrub five or six feet high, but known to reach a height of 40 feet in the mountains of North Carolina, with the habit of a tree. Wood light brown, heavy, hard, and close-grained. Not used to much extent in manufacture. Range same as the preceding.

54. Magnolia (Magnolia glauca) (Swamp Magnolia, Small Magnolia, Sweet Bay, Beaver Wood). Small-sized tree. Heartwood reddish brown, sap wood cream white. Sparingly used in manufacture. Ranges from Essex County, Mass., to Long Island, N. Y., from New Jersey to Florida, and west in the Gulf region to Texas.

55. Magnolia (Magnolia tripetala) (Umbrella Tree). A small-sized tree. Wood in its quality similiar to the preceding. It may be easily recognized by its great leaves, twelve to eighteen inches long, and five to eight inches broad. This species as well as the preceding is an ornamental tree. Ranges from Pennsylvania southward to the Gulf.

56. Cucumber Tree (Magnolia accuminata) (Tulip-wood, Poplar). Medium- to large-sized tree. Heartwood yellowish brown, sapwood almost white. Wood light, soft, satiny, close-grained, durable in contact with the soil, resembling and sometimes confounded with tulip tree (Liriodendron tulipifera) in the markets. The wood shrinks considerably, but seasons without much injury, and works and stands well. It bends readily when steamed, and takes stain and paint well. Used in cooperage, for siding, for panelling and finishing lumber in house, car and shipbuilding, etc., also in the manufacture of toys, culinary woodenware, and backing for drawers. Most common in the southern Alleghanies, but distributed from western New York to southern Illinois, south through central Kentucky and Tennessee to Alabama, and throughout Arkansas.

Wood heavy, hard, strong, stiff, and tough, of fine texture, frequently wavy-grained, this giving rise to "curly" and "blister" figures which are much admired. Not durable in the ground, or when exposed. Maple is creamy white, with shades of light brown in the heartwood, shrinks moderately, seasons, works, and stands well, wears smoothly, and takes a fine polish. The wood is used in cooperage, and for ceiling, flooring, panelling, stairway, and other finishing lumber in house, ship, and car construction. It is used for the keels of boats and ships, in the manufacture of implements and machinery, but especially for furniture, where entire chamber sets of maple rival those of oak. Maple is also used for shoe lasts and other form blocks; for shoe pegs; for piano actions, school apparatus, for wood type in show bill printing, tool handles, in wood carving, turnery, and scroll work, in fact it is one of our most useful woods. The maples are medium-sized trees, of fairly rapid growth, sometimes form forests, and frequently constitute a large proportion of the arborescent growth. They grow freely in parts of the Northern Hemisphere, and are particularly luxuriant in Canada and the northern portions of the United States.

57. Sugar Maple (Acer saccharum) (Hard Maple, Rock Maple). Medium- to large-sized tree, very common, forms considerable forests, and is especially esteemed. The wood is close-grained, heavy, fairly hard and strong, of compact structure. Heartwood brownish, sapwood lighter color; it can be worked to a satin-like surface and take a fine polish, it is not durable if exposed, and requires a good deal of seasoning. Medullary rays small but distinct. The "curly" or "wavy" varieties furnish wood of much beauty, the peculiar contortions of the grain called "bird's eye" being much sought after, and used as veneer for panelling, etc. It is used in all good grades of furniture, cabinetmaking, panelling, interior finish, and turnery; it is not liable to warp and twist. It is also largely used for flooring, for rollers for wringers and mangling machines, for which there is a large and increasing demand. The peculiarity known as "bird's eye," and which causes a difficulty in working the wood smooth, owing to the little pieces like knots lifting up, is supposed to be due to the action of boring insects. Its resistance to compression across the grain is higher than that of most other woods. Ranges from Maine to Minnesota, abundant, with birch, in the region of the Great Lakes.

58. Red Maple (Acer rubrum) (Swamp Maple, Soft Maple, Water Maple). Medium-sized tree. Like the preceding but not so valuable. Scattered along water-courses and other moist localities. Abundant. Maine to Minnesota, southward to northern Florida.

59. Silver Maple (Acer saccharinum) (Soft Maple, White Maple, Silver-Leaved Maple). Medium- to large-sized tree, common. Wood lighter, softer, and inferior to Acer saccharum, and usually offered in small quantities and held separate in the markets. Heartwood reddish brown, sapwood ivory white, fine-grained, compact structure. Fibres sometimes twisted, weaved, or curly. Not durable. Used in cooperage for woodenware, turnery articles, interior decorations and flooring. Valley of the Ohio, but occurs from Maine to Dakota and southward to Florida.

60. Broad-Leaved Maple (Acer macrophyllum) (Oregon Maple). Medium-sized tree, forms considerable forests, and, like the preceding has a lighter, softer, and less valuable wood than Acer saccharum. Pacific Coast regions.

61. Mountain Maple (Acer spicatum). Small-sized tree. Heartwood pale reddish brown, sapwood lighter color. Wood light, soft, close-grained, and susceptible of high polish. Ranges from lower St. Lawrence River to northern Minnesota and regions of the Saskatchewan River; south through the Northern States and along the Appalachian Mountains to Georgia.

62. Ash-Leaved Maple (Acer negundo) (Box Elder). Medium- to large-sized tree. Heartwood creamy white, sapwood nearly white. Wood light, soft, close-grained, not strong. Used for woodenware and paper pulp. Distributed across the continent, abundant throughout the Mississippi Valley along banks of streams and borders of swamps.

63. Striped Maple (Acer Pennsylvanicum) (Moose-wood). Small-sized tree. Produces a very white wood much sought after for inlaid and for cabinet work. Wood is light, soft, close-grained, and takes a fine polish. Not common. Occurs from Pennsylvania to Minnesota.

64. Red Mulberry (Morus rubra). A small-sized tree. Wood moderately heavy, fairly hard and strong, rather tough, of coarse texture, very durable in contact with the soil. The sapwood whitish, heartwood yellow to orange brown, shrinks and checks considerably in drying, works well and stands well. Used in cooperage and locally in construction, and in the manufacture of farm implements. Common in the Ohio and Mississippi Valleys, but widely distributed in the eastern United States.

Wood very variable, usually very heavy and hard, very strong and tough, porous, and of coarse texture. The sapwood whitish, the heartwood "oak" to reddish brown. It shrinks and checks badly, giving trouble in seasoning, but stands well, is durable, and little subject to the attacks of boring insects. Oak is used for many purposes, and is the chief wood used for tight cooperage; it is used in shipbuilding, for heavy construction, in carpentry, in furniture, car and wagon work, turnery, and even in woodcarving. It is also used in all kinds of farm implements, mill machinery, for piles and wharves, railway ties, etc., etc. The oaks are medium- to large-sized trees, forming the predominant part of a large proportion of our broad-leaved forests, so that these are generally termed "oak forests," though they always contain considerable proportion of other kinds of trees. Three well-marked kinds—white, red, and live oak—are distinguished and kept separate in the markets. Of the two principal kinds "white oak" is the stronger, tougher, less porous, and more durable. "Red oak" is usually of coarser texture, more porous, often brittle, less durable, and even more troublesome in seasoning than white oak. In carpentry and furniture work red oak brings the same price at present as white oak. The red oaks everywhere accompany the white oaks, and, like the latter, are usually represented by several species in any given locality. "Live oak," once largely employed in shipbuilding, possesses all the good qualities, except that of size, of white oak, even to a greater degree. It is one of the heaviest, hardest, toughest, and most durable woods of this country. In structure it resembles the red oak, but is less porous.

65. White Oak (Quercus alba) (American Oak). Medium- to large-sized tree. Heartwood light brown, sapwood lighter color. Annual rings well marked, medullary rays broad and prominent. Wood tough, strong, heavy, hard, liable to check in seasoning, durable in contact with the soil, takes a high polish, very elastic, does not shrink much, and can be bent to any form when steamed. Used for agricultural implements, tool handles, furniture, fixtures, interior finish, car and wagon construction, beams, cabinet work, tight cooperage, railway ties, etc., etc. Because of the broad medullary rays, it is generally "quarter-sawn" for cabinet work and furniture. Common in the Eastern States, Ohio and Mississippi Valleys. Occurs throughout the eastern United States.

66. White Oak (Quercus durandii). Medium- to small-sized tree. Wood in its quality and uses similiar to the preceding. Texas, eastward to Alabama.

67. White Oak (Quercus garryana) (Western White Oak). Medium- to large-sized tree. Stronger, more durable, and wood more compact than Quercus alba. Washington to California.

68. White Oak (Quercus lobata). Medium- to large-sized tree. Largest oak on the Pacific Coast. Wood in its quality and uses similar to Quercus alba, only it is finer-grained. California.

69. Bur Oak (Quercus macrocarpa) (Mossy-Cup Oak, Over-Cup Oak). Large-sized tree. Heartwood "oak" brown, sapwood lighter color. Wood heavy, strong, close-grained, durable in contact with the soil. Used in ship- and boatbuilding, all sorts of construction, interior finish of houses, cabinet work, tight cooperage, carriage and wagon work, agricultural implements, railway ties, etc., etc. One of the most valuable and most widely distributed of American oaks, 60 to 80 feet in height, and, unlike most of the other oaks, adapts itself to varying climatic conditions. It is one of the most durable woods when in contact with the soil. Common, locally abundant. Ranges from Manitoba to Texas, and from the foot hills of the Rocky Mountains to the Atlantic Coast. It is the most abundant oak of Kansas and Nebraska, and forms the scattered forests known as "The oak openings" of Minnesota.

70. Willow Oak (Quercus phellos) (Peach oak). Small to medium-sized tree. Heartwood pale reddish brown, sapwood lighter color. Wood heavy, hard, strong, coarse-grained. Occasionally used in construction. New York to Texas, and northward to Kentucky.

71. Swamp White Oak (Quercus bicolor var. platanoides). Large-sized tree. Heartwood pale brown, sapwood the same color. Wood heavy, hard, strong, tough, coarse-grained, checks considerably in seasoning. Used in construction, interior finish of houses, carriage- and boatbuilding, agricultural implements, in cooperage, railway ties, fencing, etc., etc. Ranges from Quebec to Georgia and westward to Arkansas. Never abundant. Most abundant in the Lake States.

72. Over-Cup Oak (Quercus lyrata) (Swamp White Oak, Swamp Post Oak). Medium to large-sized tree, rather restricted, as it grows in the swampy districts of Carolina and Georgia. Is a larger tree than most of the other oaks, and produces an excellent timber, but grows in districts difficult of access, and is not much used. Lower Mississippi and eastward to Delaware.

73. Pin Oak (Quercus palustris) (Swamp Spanish Oak, Water Oak). Medium- to large-sized tree. Heartwood pale brown with dark-colored sap wood. Wood heavy, strong, and coarse-grained. Common along the borders of streams and swamps, attains its greatest size in the valley of the Ohio. Arkansas to Wisconsin, and eastward to the Alleghanies.

74. Water Oak (Quercus aquatica) (Duck Oak, Possum Oak). Medium- to large-sized tree, of extremely rapid growth. Eastern Gulf States, eastward to Delaware and northward to Missouri and Kentucky.

75. Chestnut Oak (Quercus prinus) (Yellow Oak, Rock Oak, Rock Chestnut Oak). Heartwood dark brown, sapwood lighter color. Wood heavy, hard, strong, tough, close-grained, durable in contact with the soil. Used for railway ties, fencing, fuel, and locally for construction. Ranges from Maine to Georgia and Alabama, westward through Ohio, and southward to Kentucky and Tennessee.

76. Yellow Oak (Quercus acuminata) (Chestnut Oak, Chinquapin Oak). Medium- to large-sized tree. Heartwood dark brown, sapwood pale brown. Wood heavy, hard, strong, close-grained, durable in contact with the soil. Used in the manufacture of wheel stock, in cooperage, for railway ties, fencing, etc., etc. Ranges from New York to Nebraska and eastern Kansas, southward in the Atlantic region to the District of Columbia, and west of the Alleghanies southward to the Gulf States.

77. Chinquapin Oak (Quercus prinoides) (Dwarf Chinquapin Oak, Scrub Chestnut Oak). Small-sized tree. Heartwood light brown, sapwood darker color. Does not enter the markets to any great extent. Ranges from Massachusetts to North Carolina, westward to Missouri, Nebraska, Kansas, and eastern Texas. Reaches its best form in Missouri and Kansas.

78. Basket Oak (Quercus michauxii) (Cow Oak). Large-sized tree. Locally abundant. Lower Mississippi and eastward to Delaware.

79. Scrub Oak (Quercus ilicifolia var. pumila) (Bear Oak). Small-sized tree. Heartwood light brown, sapwood darker color. Wood heavy, hard, strong, and coarse-grained. Found in New England and along the Alleghanies.

80. Post Oak (Quercus obtusiloda var. minor) (Iron Oak). Medium- to large-sized tree, gives timber of great strength. The color is of a brownish yellow hue, close-grained, and often superior to the white oak (Quercus alba) in strength and durability. It is used for posts and fencing, and locally for construction. Arkansas to Texas, eastward to New England and northward to Michigan.

81. Red Oak (Quercus rubra) (Black Oak). Medium- to large-sized tree. Heartwood light brown to red, sapwood lighter color. Wood coarse-grained, well-marked annual rings, medullary rays few but broad. Wood heavy, hard, strong, liable to check in seasoning. It is found over the same range as white oak, and is more plentiful. Wood is spongy in grain, moderately durable, but unfit for work requiring strength. Used for agricultural implements, furniture, bob sleds, vehicle parts, boxes, cooperage, woodenware, fixtures, interior finish, railway ties, etc., etc. Common in all parts of its range. Maine to Minnesota, and southward to the Gulf.

82. Black Oak (Quercus tinctoria var. velutina) (Yellow Oak). Medium- to large-sized tree. Heartwood bright brown tinged with red, sapwood lighter color. Wood heavy, hard, strong, coarse-grained, checks considerably in seasoning. Very common in the Southern States, but occurring North as far as Minnesota, and eastward to Maine.

83. Barren Oak (Quercus nigra var. marilandica) (Black Jack, Jack Oak). Small-sized tree. Heartwood dark brown, sapwood lighter color. Wood heavy, hard, strong, coarse-grained, not valuable. Used in the manufacture of charcoal and for fuel. New York to Kansas and Nebraska, and southward to Florida. Rare in the North, but abundant in the South.

84. Shingle Oak (Quercus imbricaria) (Laurel Oak). Small to medium-sized tree. Heartwood pale reddish brown, sapwood lighter color. Wood heavy, hard, strong, coarse-grained, checks considerably in drying. Used for shingles and locally for construction. Rare in the east, most abundant in the lower Ohio Valley. From New York to Illinois and southward. Reaches its greatest size in southern Illinois and Indiana.

85. Spanish Oak (Quercus digitata var. falcata) (Red Oak). Medium-sized tree. Heartwood light reddish brown, sapwood much lighter. Wood heavy, hard, strong, coarse-grained, and checks considerably in seasoning. Used locally for construction, and has high fuel value. Common in south Atlantic and Gulf region, but found from Texas to New York, and northward to Missouri and Kentucky.

86. Scarlet Oak (Quercus coccinea). Medium- to large-sized tree. Heartwood light reddish-brown, sapwood darker color. Wood heavy, hard, strong, and coarse-grained. Best developed in the lower basin of the Ohio, but found from Minnesota to Florida.

87. Live Oak (Quercus virens) (Maul Oak). Medium- to large-sized tree. Grows from Maryland to the Gulf of Mexico, and often attains a height of 60 feet and 4 feet in diameter. The wood is hard, strong, and durable, but of rather rapid growth, therefore not as good quality as Quercus alba. The live oak of Florida is now reserved by the United States Government for Naval purposes. Used for mauls and mallets, tool handles, etc., and locally for construction. Scattered along the coast from Maryland to Texas.

88. Live Oak (Quercus chrysolepis) (Maul Oak, Valparaiso Oak). Medium- to small-sized tree. California.

89. Osage Orange (Maclura aurantiaca) (Bois d'Arc). A small-sized tree of fairly rapid growth. Wood very heavy, exceedingly hard, strong, not tough, of moderately coarse texture, and very durable and elastic. Sapwood yellow, heartwood brown on the end face, yellow on the longitudinal faces, soon turning grayish brown if exposed. It shrinks considerably in drying, but once dry it stands unusually well. Much used for wheel stock, and wagon framing; it is easily split, so is unfit for wheel hubs, but is very suitable for wheel spokes. It is considered one of the timbers likely to supply the place of black locust for insulator pins on telegraph poles. Seems too little appreciated; it is well suited for turned ware and especially for woodcarving. Used for spokes, insulator pins, posts, railway ties, wagon framing, turnery, and woodcarving. Scattered through the rich bottoms of Arkansas and Texas.

90. Papaw (Asimina triloba) (Custard Apple). Small-sized tree, often only a shrub, Heartwood pale, yellowish green, sapwood lighter color. Wood light, soft, coarse-grained, and spongy. Not used to any extent in manufacture. Occurs in eastern and central Pennsylvania, west as far as Michigan and Kansas, and south to Florida and Texas. Often forming dense thickets in the lowlands bordering the Mississippi River.

91. Persimmon (Diospyros Virginiana). Small to medium-sized tree. Wood very heavy, and hard, strong and tough; resembles hickory, but is of finer texture and elastic, but liable to split in working. The broad sapwood cream color, the heartwood brown, sometimes almost black. The persimmon is the Virginia date plum, a tree of 30 to 50 feet high, and 18 to 20 inches in diameter; it is noted chiefly for its fruit, but it produces a wood of considerable value. Used in turnery, for wood engraving, shuttles, bobbins, plane stock, shoe lasts, and largely as a substitute for box (Buxus sempervirens)—especially the black or Mexican variety,—also used for pocket rules and drawing scales, for flutes and other wind instruments. Common, and best developed in the lower Ohio Valley, but occurs from New York to Texas and Missouri.

Wood light, very soft, not strong, of fine texture, and whitish, grayish to yellowish color, usually with a satiny luster. The wood shrinks moderately (some cross-grained forms warp excessively), but checks very little in seasoning; is easily worked, but is not durable. Used in cooperage, for building and furniture lumber, for crates and boxes (especially cracker boxes), for woodenware, and paper pulp.

92. Cottonwood (Populus monilifera, var. angulata) (Carolina Poplar). Large-sized tree, forms considerable forests along many of the Western streams, and furnishes most of the cottonwood of the market. Heartwood dark brown, sapwood nearly white. Wood light, soft, not strong, and close-grained. Mississippi Valley and West. New England to the Rocky Mountains.

93. Cottonwood (Populus fremontii var. wislizeni). Medium- to large-sized tree. Common. Wood in its quality and uses similiar to the preceding, but not so valuable. Texas to California.

94. Black Cottonwood (Populus trichocarpa var. heterophylla) (Swamp Cottonwood, Downy Poplar). The largest deciduous tree of Washington. Very common. Heartwood dull brown, sapwood lighter brown. Wood soft, close-grained. Is now manufactured into lumber in the West and South, and used in interior finish of buildings. Northern Rocky Mountains and Pacific region.

95. Poplar (Populus grandidentata) (Large-Toothed Aspen). Medium-sized tree. Heartwood light brown, sapwood nearly white. Wood soft and close-grained, neither strong nor durable. Chiefly used for wood pulp. Maine to Minnesota and southward along the Alleghanies.

96. White Poplar (Populus alba) (Abele-Tree). Small to medium-sized tree. Wood in its quality and uses similar to the preceding. Found principally along banks of streams, never forming forests. Widely distributed in the United States.

97. Lombardy Poplar (Populus nigra italica). Medium- to large-sized tree. This species is the first ornamental tree introduced into the United States, and originated in Afghanistan. Does not enter into the markets. Widely planted in the United States.

98. Balsam (Populus balsamifera) (Balm of Gilead, Tacmahac). Medium- to large-sized tree. Heartwood light brown, sapwood nearly white. Wood light, soft, not strong, close-grained. Used extensively in the manufacture of paper pulp. Common all along the northern boundary of the United States.

99. Aspen (Populus tremuloides) (Quaking Aspen). Small to medium-sized tree, often forming extensive forests, and covering burned areas. Heartwood light brown, sapwood nearly white. Wood light, soft, close-grained, neither strong nor durable. Chiefly used for woodenware, cooperage, and paper pulp. Maine to Washington and northward, and south in the western mountains to California and New Mexico.

100. Sassafras (Sassafras sassafras). Medium-sized tree, largest in the lower Mississippi Valley. Wood light, soft, not strong, brittle, of coarse texture, durable in contact with the soil. The sapwood yellow, the heartwood orange brown. Used to some extent in slack cooperage, for skiff- and boatbuilding, fencing, posts, sills, etc. Occurs from New England to Texas and from Michigan to Florida.

101. Sourwood (Oxydendrum arboreum) (Sorrel-Tree). A slender tree, reaching the maximum height of 60 feet. Heartwood reddish brown, sapwood lighter color. Wood heavy, hard, strong, close-grained, and takes a fine polish. Ranges from Pennsylvania, along the Alleghanies, to Florida and Alabama, westward through Ohio to southern Indiana and southward through Arkansas and Louisiana to the Coast.